We Begin Again: On Shabbat, October 14, 2023, Albuquerque Jews (and a few million others) were privileged to be able to observe - right over our heads, at the 2023 Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta - an annular solar eclipse.

In which the moon did not entirely block the sun, but instead obscured all but a "ring of fire" that continued to light our world.

Exactly one week before this rare and exciting event, Albuquerque Jews (and a few million others) were horrified to be able to observe - in our own homeland - the most terrifying murder of our fellow Jews since the Holocaust.

What can we learn from these two events, so diametrically opposed? Abq Jew is (as you may have noticed) no darshan, but is able to offer the following:

- Every now and then, an eclipse does happen.

- The sun shines fully before an eclipse, and shines again afterward.

- Even during an eclipse, the sun is still shining; we just can't see it.

- An eclipse lasts but a short time; the sun and moon are forever.

And yet we Jews are shaking right now.

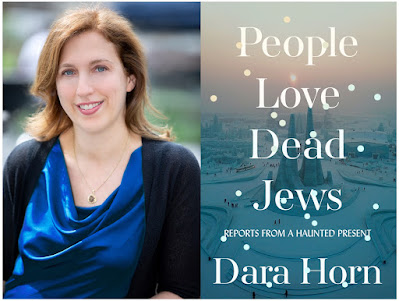

As Dara Horn wrote this week in The New York Times.

Why Jews Cannot Stop Shaking Right Now

There is a reason so many Jews cannot stop shaking right now. The concept of intergenerational trauma doesn’t begin to describe the dark place into which this month’s attack plunged Jewish communities around the world.

On Oct. 7, a Jewish holiday, Hamas terrorists went house to house in southern Israel murdering and abducting children and grandparents, pulling them from their beds, displaying victims’ dead bodies online, in a massacre of at least 1,400 people. In at least one instance, terrorists were reported to have uploaded a video of the murder of one victim to her own social media account for her family to discover.

The feeling of deep dread that these atrocities stirred in Jews was horribly familiar. This is what Jewish history has all too often looked like: not civilians tragically killed in war but civilians publicly targeted, tortured and murdered, with the crimes put on public display.

Accounts of past crowd-pleasing killings are folded into Jewish tradition; every Yom Kippur, we recount the public torture and execution of rabbis by their Roman oppressors in a packed second-century stadium. Those ancient stories are consistent with the experiences of the more immediate ancestors of nearly every Jew alive today.

I’m not even talking about the Holocaust, which several of last week’s oldest escapees and victims also endured. (Far more Jews were killed on Oct. 7 than on Kristallnacht.)

No, I’m thinking of the Farhud pogrom in 1941 Baghdad, a two-day rampage in which hundreds of Jews were raped, tortured and murdered. I’m thinking of the pogroms of 1918 to 1921 in Ukraine, in which an estimated 100,000 Jews were slaughtered in organized massacres, reminiscent of this month’s attack.

I’m thinking of the lynching of Leo Frank in Georgia in 1915, after which the delighted crowd’s snapshots of Frank’s body were made into postcards mailed around the country and pieces of his clothing were sold as souvenirs.

I’m thinking of how many of the earliest books off Europe’s first printing presses were about the executions of Jews accused of blood libel and of a 10th-century massacre of thousands of Jews in the Spanish caliphate encouraged by a poem calling for Jewish blood and of the paintings and illuminated manuscripts showing Jews who were burned alive by the Spanish Inquisition and during the Black Death — all crowd-pleasing events celebrated in popular media and art.

Even ancient Romans celebrated their destruction of Judea by issuing commemorative coins featuring a bound Jewish woman and inscribed with the words “Judaea capta.” The humiliation and murder of Jews have always made a great meme.

Many American Jews, like Jews around the world, are descendants of those who survived. Our ancestors, in one way or another, were the ones who either made lucky decisions or barely made it out alive from Lodz and Kyiv and Aleppo and Tehran.

For diaspora Jews, the recent attacks were not distant overseas events. As was true in ancient times, the ties between global Jewish communities and Israel are concrete, specific, intimate and personal.

My New Jersey Jewish Federation has institutional ties with the southern Israeli town of Ofakim and its surrounding communities, sharing annual home stays with a place whose death toll from the attacks already exceeds that of the notorious Kishinev pogrom of 1903, in which 49 Jews were murdered.

Millions of American Jews, not to mention Jews in Britain, France, Australia and elsewhere, have friends and relatives in Israel. Even if Hamas hadn’t made it clear that they see all Jews as targets, our connection is personal and all too real.

We spent days desperately scrolling to learn who among our acquaintances was dead, maimed or captive, connecting American hostages’ families with State Department contacts, attending panic-stricken online briefings and pooling resources and supplies for victims — all while fighting obtuse official statements from our own towns, schools, companies and universities that refused to mention the words “Israel” or “Jews” in referring to the largest single-day massacre of Jews since the Holocaust, lest some antisemite take offense at the existence of either.

We have tried to get our children off social media, shielding them from images of the violence. We’ve held mass fasts, recited psalms and sung ancient prayers for the rescue of captives.

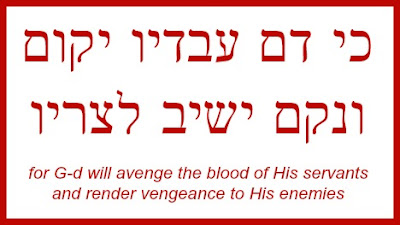

And as we gather by the thousands despite our many contradictory opinions and despite the extra security required for our gatherings even here, we have returned to the words of our ancestors that have carried us through thousands of years:

Be strong and courageous. Choose life.

Many of us were physically carrying those words during the weekend of the attack, celebrating Simchat Torah, a joyous holiday when congregations dance with Torah scrolls, read the Torah’s final words and then scroll back to the beginning to start the book again.

As a child, I found this baffling. Why read the same story over and over, when we already know what happens? As an adult, I know that while the story doesn’t change, we do.

What defines Jewish life is not history’s litany of horror but the Jewish people’s creative resilience in the face of it.

In the wake of many catastrophes over millenniums, we have wrestled with God and one another, reinvented our traditions, revived our language, rebuilt our communities and found new meanings in our old stories of freedom and responsibility, each story animated by the improbable and unwavering belief that people can change.

Right now many of us feel trapped in this old, old story, doom-scrolling through images with terrible outcomes.

But in our grief, I remind myself that each year as we finish the reading of the Torah, we immediately, at that very moment — and at the moment of this newest, oldest horror — scroll back to the story of creation and the invention of universal human dignity.

We recall, once again, thatevery human is made in the divine image.

The story continues; we begin again.

And yet in Israel, there are weddings - many, many weddings - taking place. Simcha - joy - takes precedence over mourning.

There is a story in the Talmud of two processions – a wedding procession and a funeral procession – that meet at an intersection too narrow to allow both to pass. One of the processions will need to step aside to allow the other to progress; but which one should go first?

The rabbis concluded that the wedding procession should get the right of way. Why? Because hope and optimism about the future (as represented by the bride and groom) should always take precedence over the past. We are a people who believe in the future – even in the face of sadness.

In the midst of rage and pain and loss,

take a breath and a moment

to renew your soul with the beauty of the world,

the love of others who care, and the recognition

of that which is greater than any of us.