Rereading Dara Horn: It is only six very short years since Abq Jew personally encountered antisemitic hate on his blog and website (see You've Got Hate Mail! and Documenting Hate). The story even made it to The New York Times - a decidedly mixed blessing.

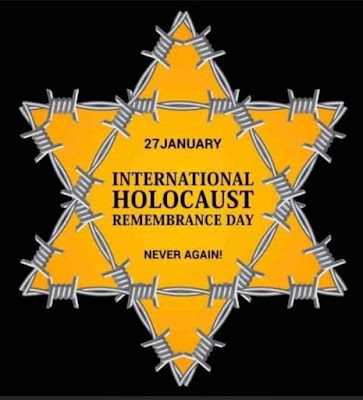

So much has happened since then. And so little has changed. If anything, antisemitism here in our beautiful US of A, where we recently observed International Holocaust Remembrance Day, has only increased. But we NewMexiJews know all too well -

For us, every day is Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Horn’s main insight is that much of the way we’ve developed to remember and narrate Jewish history is, at best, self-deception and, at worst, rubbish.

The 12 essays in her brilliant book explore how the different ways we commemorate Jewish tragedy, how we write about the Holocaust, how the media presents antisemitic events, how we establish museums to honor Jewish heritage, how we read literature with Jewish protagonists and even how we praise the “righteous among the nations” (those who saved Jews during the war), are all distractions from the main issue, which is the very concrete, specific death of Jews.

Even though each chapter reveals a different blind spot in our collective memory — ranging from Horn’s visit to the Museum of Jewish Heritage in downtown Manhattan to her travel to the Jewish sites in Harbin, China — all the essays in the book show that when we learn to remember certain things in certain ways, we set the limits of what can be said, and what cannot be said, even as we might have the urge to say it.

Horn thinks it’s about time to say it, and this is why her book is at the same time so necessary and so disquieting.

Dara Horn's opening essay, Everyone's (Second) Favorite Dead Jew, gets right to the point. The essay was published in the November 2018 issue of The Smithsonian as Becoming Anne Frank. It begins:

People love dead Jews. Living Jews, not so much.

This disturbing idea was suggested by an incident this past spring at the Anne Frank House, the blockbuster Amsterdam museum built out of Frank’s “Secret Annex,” or in Dutch, “Het Achterhuis [The House Behind],” a series of tiny hidden rooms where the teenage Jewish diarist lived with her family and four other persecuted Jews for over two years, before being captured by Nazis and deported to Auschwitz in 1944.

Here’s how much people love dead Jews: Anne Frank’s diary, first published in Dutch in 1947 via her surviving father, Otto Frank, has been translated into 70 languages and has sold over 30 million copies worldwide, and the Anne Frank House now hosts well over a million visitors each year, with reserved tickets selling out months in advance.

But when a young employee at the Anne Frank House in 2017 tried to wear his yarmulke to work, his employers told him to hide it under a baseball cap. The museum’s managing director told newspapers that a live Jew in a yarmulke might “interfere” with the museum’s “independent position.”

The museum finally relented after deliberating for six months, which seems like a rather long time for the Anne Frank House to ponder whether it was a good idea to force a Jew into hiding.

And so here we are, once again, talking about Anne Frank. And the book's title.

The line most often quoted from Frank’s diary—“In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”—is often called “inspiring,” by which we mean that it flatters us.

It makes us feel forgiven for those lapses of our civilization that allow for piles of murdered girls—and if those words came from a murdered girl, well, then, we must be absolved, because they must be true.

That gift of grace and absolution from a murdered Jew (exactly the gift, it is worth noting, at the heart of Christianity) is what millions of people are so eager to find in Frank’s hiding place, in her writings, in her “legacy.”

It is far more gratifying to believe that an innocent dead girl has offered us grace than to recognize the obvious:

Frank wrote about people being “truly good at heart” three weeks before she met people who weren’t.

Dead Jews are supposed to teach us about the beauty of the world and the wonders of redemption - otherwise, what was the point of killing them in the first place? That's what dead Jews are for!

For the record, the number of actual "righteous Gentiles" officially recognized by Yad Vashem, Israel's national Holocaust museum and research center, for their efforts in rescuing Jews from the Holocaust is under 30,000 people, out of a European population at the time of nearly 300 million - or .001 percent.

Even if we were to assume that the official recognition is an undercount by a factor of ten thousand, such people remain essentially a rounding error.

As Abq Jew is sure you can plainly see from the excerpts he has thoughtfully provided, People Love Dead Jews is not an easy book to read. But it is an important book - "an outstanding book with a bold mission. It criticizes people, artworks and public institutions that few others dare to challenge."

Jewish Review of Books editor Abraham Socher

No comments:

Post a Comment