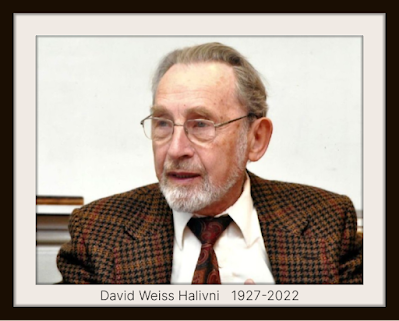

The Chosen: Rabbi David Weiss Halivni, a theologian, beloved teacher, and pioneer in the field of academic Talmudic scholarship, died Wednesday [June 29] at age 94 in Israel.

David Weiss Halivni, pillar of Talmudic scholarship, Holocaust survivor, dies age 94

A prodigy, Halivni received rabbinic ordination at 15, won the Israel Prize and molded generations of scholars in US and Israel, teaching well into his 90s

Prof. David Weiss Halivni, a theologian and pioneer in the field of academic Talmudic scholarship, died Wednesday at age 94.

Born in today’s Ukraine, Halivni was raised in Sighet, Romania, by a Talmudic scholar grandfather who fostered his evident genius with rabbinic texts. In Sighet, he studied alongside Elie Wiesel, who remained a close, lifelong friend.

Halivni was ordained as a rabbi at 15, but by the age of 16, he was captured by the Nazis, and, like Wiesel, was sent to Auschwitz and a series of Nazi camps.

“We were in the ghetto together. He was on the last transport. I was on the first. I left on Monday, he left Thursday,” said Halivni in an obituary for Weisel.

“So we came to Auschwitz at different times.”

Halivni was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust....

Orphaned, Halivni started life in New York, where his scholarship began anew, eventually at the Jewish Theological Seminary under Rabbi Saul Lieberman. Halivni taught at JTS until 1983 and left over the issue of the ordination of women, moving to Columbia University from where he retired in 2005.

After his retirement, he moved to Israel, where he continued to teach at Hebrew University and Bar Ilan University well into his 90s. In 2008, Halivni was awarded the Israel Prize for his Talmudic work.

Halivni was a daily presence at the National Library in Israel, where he continued his research until just before the coronavirus pandemic.

In his autobiography The Book and the Sword, Halivni writes that he taught in the concentration camps and even risked his life to save a scrap of paper from a sacred book. However, he recoiled from those who attempted to explain the Holocaust through theological terms.

Later, in his collection of essays Breaking the Tablets: Jewish Theology After the Shoah, Halivni radically proposes that God revealed Himself to the Jewish people twice: once at Mount Sinai with the revelation of presence, and once at Auschwitz with the revelation of utter and complete absence, in which humans were given total and complete free will.

Wikipedia offers a few interesting details:

When he arrived in the United States at the age of 18, he was placed in a Jewish orphanage where he created a stir by challenging the kashrut of the institution since the supervising rabbi did not have a beard and, more importantly, was not fluent in the commentaries of the Pri Megadim by Rabbi Yoseph Te'omim. This was a standard for Rabbis in Europe.

A social worker introduced him to Saul Lieberman, a leading Talmudist at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTS) in New York, who recognized his brilliance and took him under his wing. Weiss later studied with Lieberman for many years at the JTS.

[Halivni] earned a bachelor's degree in philosophy from Brooklyn College, and a Master's Degree in philosophy from NYU; he wrote his Doctorate in Talmud at JTS.

And this:

Halivni was involved in the 1983 controversy at JTS surrounding the training and ordination of women as rabbis.

He felt that there may be halakhic methods for ordaining women as rabbis, but that more time was needed before such could be legitimately instituted, and that the decision had been made as a policy decision by the governing body of the Seminary rather than as a psak halachah within the traditional rabbinic legal process.

This disagreement led to his break with the seminary and with the movement of Conservative Judaism, and to his co-founding of the Union for Traditional Judaism and its yeshiva, the Institute of Traditional Judaism.

For those who are too young to remember or too old to recall, Wikipedia reminds us:

The Chosen is a novel written by Chaim Potok. It was first published in 1967. It follows the narrator, Reuven Malter, and his friend Daniel Saunders, as they grow up in the Williamsburg neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York, in the 1940s.

A sequel featuring Reuven's young adult years, The Promise, was published in 1969. The Chosen was made into a movie in 1981.

One of Potok's major themes is the struggle between holding on to the traditions of one's culture in an ever-changing world and taking on the culture of the adopted home country. And his main character is Reuven (Robert or Bobby) Malter: a Modern Orthodox Jew, and a teenage boy.

Reuven is smart, popular in his community, and has a head for mathematics and logic. His father wants him to be a mathematician when he grows up, but he desires to become a rabbi.

When Abq Jew studied at JTS, everyone "knew" that

Rabbi David Weiss Halivni was Reuben Malter.

In 2017, on the 50th Anniversary of The Chosen's publication, Aaron R Katz published his reflections on the novel in Tablet Magazine.

Some Reflections on Chaim Potok’s ‘The Chosen’

The novel, published 50 years ago today, shaped the American Jewish encounter with Hasidism and Orthodoxy, while giving a pretty good play-by-play account of a baseball game

Fifty years ago today, on April 28, 1967, Chaim Potok’s first novel, The Chosen, was published. It would stay on The New York Times best-seller list for 39 weeks and become a finalist for a National Book Award in 1968.

Despite the passage of time, the novel has continued to stay in the public eye ... Like many Jewish day-school graduates, I first encountered the novel as a reading assignment in the eighth grade some 20 years ago. I could not put it down.

Potok crafted a marvelous story in which the worlds of two Williamsburg boys from two distinct communities, one Hasidic and one Modern Orthodox, collide due to a chance meeting on a baseball diamond.

Katz continues, going deeper:

In evaluating the novel’s impact on my own life, I’m most drawn to the personal religious struggle of the protagonist, Malter. Perhaps Malter’s struggle is meant to autobiographically reflect the real tensions Potok himself experienced.

Indeed, the similarities between Potok and Reuven Malter are readily apparent throughout the book.

And then there's Rabbi David Weiss Halivni:

One of the people whom Potok thanks on the opening page of The Promise is professor David (Weiss) Halivni, a Holocaust survivor and longtime Talmud professor at JTS and Columbia University who is universally acclaimed as one of the pioneers of the academic Talmudic approach.

And, Katz tells us:

Halivni lives in the Shaarei Chessed neighborhood in Jerusalem, and I recently saw him one Shabbos morning at the Kahal Chassidim synagogue.

While it may seem strange to run into one of the foremost academic Talmudists davening at an Ultra-Orthodox shul in Jerusalem, where the congregants would not generally support his scholarly approach, in praying there, Halivni is true to the sentiments he expressed in his 1983 resignation letter to JTS:

“It is my personal tragedy that the people I daven with, I cannot talk to, and the people I talk to, I cannot daven with. However, when the chips are down, I will always side with the people I daven with; for I can live without talking. I cannot live without davening.”

After davening that Shabbos morning, I went up to Halivni to ask him about his relationship with Potok. After exchanging warm greetings and expressing his joy in being recognized, Halivni discussed the many ways the fictional Malter and the Talmudic methodology he uses in The Chosen were modeled after him and his own personal work.

With a warm smile and a wink, Halivni told me:

“I am Reuven Malter.”

Of course Rabbi Halivni is Reuven Malter. What a shame that he couldn't talk to the people he davened with and couldn't daven with the people talked to. I was so taken with those characters inspired by Chaim Potok that I have written a wholly transformative novel that ages them into young adults in Brooklyn in the 1950s, "The Choice: A Novel of Love, Faith and Talmud."

ReplyDelete