Going to Services Should Not Be: No, Abq Jew does not want to blog about the Congregation Beth Israel hostage taking, standoff, or escape.

Others, with more knowledge and insight than Abq Jew - from the JTA and The Forward to mainstream newspapers and even TV - have covered the topic. And will probably continue to cover the topic, as long as an antisemitic attack on a US synagogue in 2022 America is considered newsworthy.

There are a few things that Abq Jew feels he should present to you, his loyal readers, as part of the historical record.

The first is the PBS NewsHour's excellent synopsis of last Shabbat's events in Colleyville, Texas.

This weekend's events in Texas where four people were taken hostage at a synagogue have renewed concerns about potential targeting of groups and the threats of anti-Semitism. Amna Nawaz reports on how this latest anti-Semitic incident is impacting the Jewish community, and what it says about the state of hate in America more broadly.

Next is a Guest Essay in The New York Times by Dr Deborah E Lipstadt. As many of you know, Dr Lipstadt is a professor of modern Jewish history and Holocaust studies at Emory University.

You may also know that Dr Lipstadt has been nominated by President Biden to be the State Department Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism. Senate Republicans have refused - for months, now - to consider her nomination (or Emergency Iron Dome funding).

Why It’s Scary to Be Jewish in America Today

Jan. 18, 2022 By Deborah E. Lipstadt

Baruch atah Adonai, eloheinu melech ha-olam,matir asurim.Blessed are you, God, sovereign of the universe,who frees the captives.

Look in virtually any prayer book of any stream of Judaism and you will find this prayer in the section known as Blessings of the Dawn. The invocation comes right at the beginning. So integral is this idea to the Jewish psyche, we praise God again for freeing captives during the Amidah, one of the liturgy’s most central prayers.

Late Saturday night, as news came of the safe conclusion of the hostage-taking at Congregation Beth Israel in Colleyville, Texas, I — together with many other Jews around the world — recited that blessing. Tears, for many of us, flowed freely. We shared it. We posted it. We felt it.

Another tragedy had been averted. But the scars remain. They will take a long time to heal. I thought of the Beth Israel rabbi’s two daughters who waited all day to hear of their father’s fate. One rabbi recently told me that some of her colleagues’ children don’t want them to be congregational rabbis anymore. “It’s too dangerous.” They don’t want to have to worry every time their parent goes to the office. The parent’s office is the synagogue.

My rabbi, Adam Starr, posted to Facebook that on Sunday morning, when he went into synagogue for daily prayer, it felt like “an act of courage, defiance and faith.” Another friend told me that whenever she walks into a synagogue she makes a mental check of the nearest exit and figures out where the safest place to hide is. Under a pew? In a storage closet? Behind the ark, which holds the sacred Torah scrolls? She was shocked when I said I don’t do that. Yet.

Jews have learned to be afraid beyond the synagogue. In May during the Gaza conflagration, people eating at a kosher restaurant in Los Angeles were beaten up by a mob. In London, a phalanx of cars moved through Jewish neighborhoods chanting “Kill Jews, rape their daughters.” In Times Square in New York, a Jew wearing a kipa, or skullcap, was punched and pepper-sprayed.

When the attack is on a synagogue, during prayer, the pain is particularly intense. Each incident of vandalism — antisemitic graffiti at a Tucson synagogue, desecration of synagogues in the Bronx in the spring — or worse, arson at an Austin, Texas, synagogue this fall, is felt by Jews far beyond the confines of that specific community.

Jews have long thought of their synagogues as both a place to pray and a place to find community. As Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker noted after his heroic escape from the gunman in Colleyville, a synagogue is called a beit knesset, a house of gathering. That is why, when traveling abroad, even Jews who are not regular synagogue attendees often seek out the local synagogue.

For decades, when I got directions to synagogues in countries outside my own — be it in Germany, Turkey, Poland, Italy or Colombia — I would be advised that, to make my search easier, I didn’t have to know the precise address. When I got to the street on which the building was situated, I was told, I should just look for the police officers with the submachine guns. That’s where the synagogue would be. Also: Bring my passport. And be prepared for questions.

In some cities, synagogues ask that you call ahead to let them know you are coming. In Stockholm two years ago, the guard outside had been alerted to my coming. But he took no chances. So I found myself on a snowy street, reciting select prayers for him. Only after proving my bona fides did he let me in.

That was once an experience limited to when I traveled abroad. Now American Jews like myself experience it at home — in our own synagogues, and in those we attend in American cities across this country. We look across the street at the big church and can’t help but notice that there are no guards there.

A couple of summers ago, I was in the Berkshires on a Sunday morning driving through one of those innumerable picturesque small towns. Along the way, I passed a large church, right on the main street. It dated back to Revolutionary times. Something seemed off to me. The four large entry doors were wide open. Congregants stood happily greeting people as they entered. Then I realized what was discordant. No armed guard. No security check. No one told to “please use the side entrance, because it’s more secure.” Just an open invitation: Come in. Welcome.

I have not walked through the main entrance to my synagogue since October 2018, after the shootings at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue. For over three years now, that door has remained locked. When I asked why, I was told, “It’s too wide open; it can’t be made secure.” I understood. You won’t find wide-open doors at any synagogue in Europe or North America. It is only after you get past the guards that you find welcome, though welcome is still there for those who seek it.

It is not just the large synagogues that fear for security. I hear from students that they think twice about going to Hillel services, the campus Jewish chaplaincy. Some out of fear for physical safety. Some out of worry about the slings and barbs that might come from other students in the dorm. I met parents whose child had been accepted to a very selective college. He wears a kipa and was struggling with whether to replace it for the next four years with a baseball cap. Increasingly I hear: Jews are contemplating going underground.

We are shaken. We are not OK. But we will bounce back. We are resilient because we cannot afford not to be. That resiliency is part of the Jewish DNA. Without it, we would have disappeared centuries ago. We refuse to go away. But we are exhausted.

Rabbi Cytron-Walker credited his survival to the active-shooter training and security courses that he and his congregants took in order to prepare for just such a moment. He knew to stay calm and knew the right moment to fling a chair at his captor and dash for the exit with the other captives. The Jewish community offers such training on a regular basis to an array of Jewish institutions, especially to our synagogues and our schools.

It is not radical to say that going to services, whether to converse with God or with the neighbors you see only once a week, should not be an act of courage. And yet this weekend we were once again reminded that it can be precisely that.

Among those morning blessings that are part of Blessings of the Dawn is one that thanks God for opening up the eyes of the blind. Jewish eyes did not need to be opened. But this week we wonder if the eyes of our non-Jewish friends and neighbors, particularly the ones who didn’t call to see if we were OK, have been opened just a bit.

There is an additional blessing during these early prayers that thanks God for allowing us to stand tall and straight. We are standing tall and we are standing straight.

But we are checking for the exits.

Next: Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker's interview on CBS Mornings.

Texas Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker joined "CBS Mornings" on Monday to share his story of survival during this weekend's hostage crisis at a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas.

And: hostage Jeffrey Cohen's interview on MSNBC.

Jeffrey Cohen, one of the Texas synagogue hostages, speaks out about his experience during the 11-hour standoff and explains how he and two others managed to escape unharmed. He also mentions that he believes the hostage-taker was mentally ill by the way he was acting.

The Jewish Federation of New Mexico issued a statement and sponsored a community vigil at Congregation Albert, which was covered by KOB4.

Shalom Friends,

As we recover from the shocking experience and trauma experienced by the hostages at Congregation Beth Israel in Texas, our community shared a collective sigh of relief and gratitude that this horrible event did not end in tragedy and the hostages were freed safe and sound. We can only imagine the painful trauma of their experience and pray for their healing and wellbeing.

In consultation with the Secure Community Network of the Jewish Federations of North American, throughout the incident we were apprised with security advisories. In addition, we were on standby for alerts from our local FBI and the Joint Terrorism Task Force with whom JFNM has regular and ongoing communication.

Today I received a call from FBI Special Agent in Charge for Albuquerque, Raul Bujanda, reaching out to our community to extend his support and inquire how our local community has been responding.

He also indicated that the FBI is investigating the incident with specific interest in the motive of the perpetrator, whether the individual was a lone wolf or connected in any way to a terrorist network that may have figured in his motivation.

The investigation is international and ongoing. He reiterated their vigilance in protecting our local Jewish community from any future hate crime.

It is prudent for all Jewish organizations, synagogues, and facilities to remain on heightened security alert, not in response to any specific threat, but as best practice following this incident.

Thank you to Congregation Albert for organizing a meaningful community vigil of prayer, music and reflection expressing our solidarity with Congregation Beth Israel in Texas. It was wonderful healing moment for our community.

Also, FYI, please watch a report given on KOB4 which provided an opportunity for JFNM to share our concerns, relief and message of response to our entire regional community at this link.

With continuing prayers and gratitude let us all remain situationally aware and safe.

L’shalom,

David Blacher, President Rabbi Dr. Rob Lennick, CEO

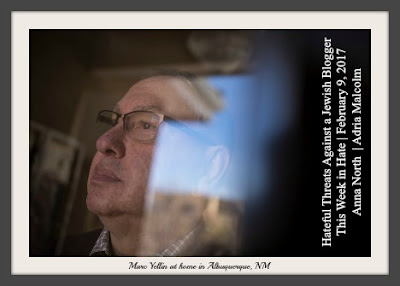

January 2017 was before the hate attack in Portland; before the hateful Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville; before the hate attack on the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh; before the hate attack on Chabad of Poway; before the hate attack in Jersey City; and before the hate attack in Monsey.

We were all so much younger then.

|

There are some things Abq Jew will never forget. |

No comments:

Post a Comment